|

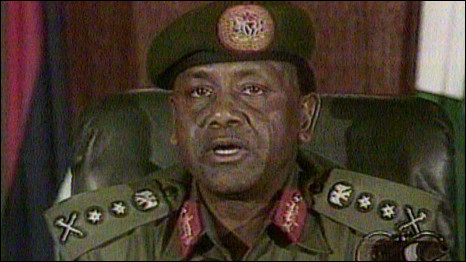

| Gen. Sani Abacha |

The

complex military intrigues associated with the Sani Abacha led Palace coup of

November 17, 1993 and its aftermath reminds me of three lines in Chapter IV

of "The Art of War" by the Chinese Military

Philosopher Sun Tzu, under 'TACTICAL DISPOSITIONS':

“1. Sun

Tzu said: The good fighters of old first put themselves beyond the possibility

of defeat, and then waited for an opportunity of defeating the enemy.

2. To

secure ourselves against defeat lies in our own hands, but the opportunity of

defeating the enemy is provided by the enemy himself.

15. Thus

it is that in war the victorious strategist only seeks battle after the victory

has been won, whereas he who is destined to defeat first fights and afterwards

looks for victory.”

COUNT-DOWN TO THE NOVEMBER 17 COUP

FROM 1985

- 1990

When

Major General Ibrahim Babangida came to power after the Palace Coup of August

1985, he rewarded then Major General Sani Abacha, GOC of the Army’s

2nd Division with the position of Chief of Army Staff - the position from

which Babangida had launched himself into power. Abacha reportedly

negotiated for this position as a condition for supporting the coup.

However,

Abacha was not well regarded professionally. He was thought of as a

very dull officer, who was prone to late coming, disliked staff meetings, kept

odd hours, enjoyed exclusive private parties and loved entertaining himself

with curious personal interests. There were rumors that he had not

made it out of the Staff College at Jaji with honor, that some of his old

confidential reports were much below par and that he had been saved on several

occasions from retirement during his military career. One such occasion was a

controversial bloody clash with the Police when he was the Brigade Commander in

Port Harcourt in the late seventies. Nevertheless, he was a key coup

conspirator in December 1983 and August 1985 - which is what counted in the

Nigerian Army of that era.

According

to sources, soon after he became Army Chief in 1985 one of the first things he

did was intimidate many local and foreign Army contractors into arrangements

from which he would benefit personally. Some of those who met

him then say he seemed to be driven by a fanatical desire to compete

financially with his rival and protégé, General Babangida, who had been the

immediate past holder of that office. A source told me that Abacha -

without providing any evidence - had a mental fixation that Babangida was very

wealthy and that he (Abacha) could also be wealthy if contractors “do for me as you did for him”. The

dysfunctional manifestations of this rivalry dogged Abacha throughout his

career as a Service Chief and later Head of State. Allegedly he

always felt that he needed to stash away huge sums of money as a way to

guarantee his personal security. It remains unclear to this day why

he felt that way.

He was

also very state-security conscious and regularly took a hard line against

soldiers suspected of disloyalty. He was party to the decision to

execute General Vatsa and others in March 1986 - in spite of numerous domestic

and foreign pleas - and was not happy when the charge against Major Akinyemi

was changed from ‘Treason’ to ‘treasonable felony’. His displeasure

was that the lesser charge guaranteed that even if guilty he would not be

executed. (Never a man to forget old grudges, he stubbornly refused

to release the Major from Prison ten years later, even after he completed his

sentence!)

In time,

Abacha’s poor management skills and lack of professional respect undermined him

with the caucus of junior and middle ranking officers that brought Babangida to

power. As the Chief of Army Staff, he was even allegedly personally

insulted by then Major Sambo Dasuki, a one-time ADC to the President - an

incident that eventually led to the Major’s first “protective exile” to the

United States on course. Clamour began that Abacha

be removed as Army Chief to make way for a more professionally sound

officer. I vividly recall an officer (now late) tell me back then

that “Abacha is spoiling the Army.” Naturally, once his blood was

sensed in the water, other ambitious senior Army Officers began eyeing his job,

notably Brigadier (later Major General) Joshua Dogonyaro who had also been a

key insider in the coup that propelled Babangida to power. Not far

behind were other Officers of the Regular One- (1) course at the Nigerian

Defence Academy who felt that their time had come to take over the leadership

of the Army from foreign-trained Officers. Such Regular One Officers

included Saliu Ibrahim, Aliyu Gusau, Oladipo Diya, etc.

Abacha’s

reaction to all this was to accuse Babangida of deliberately underfunding the

Army so as to make him (Abacha) unpopular with the troops. Things

were bad enough at one stage that a secret meeting of insiders outside the

context of the Armed Forces Ruling Council had to be held at Ikeja Cantonment

to smooth things over. Sources claim special financial arrangements

were made to placate Abacha and allay his suspicions, while alternative

mechanisms - like adhoc Task Forces - were later created to ensure

that funds actually reached operational units, bypassing the Ministry of Defence.

Nevertheless,

clamour continued for Abacha’s removal. Eventually, General Babangida concocted

a dicey two step scheme to do so. The scheme involved the

initial removal of Lt. General Domkat Bali as concurrent Chairman,

Joint Chiefs of Staff and Minister of Defence. In this

scenario, Babangida became the Defence Minister while Abacha was to

simultaneously hold the positions of Chief of Army Staff and Chairman, Joint

Chiefs of Staff. Step Two (2) would involve Babangida giving

up the Defence Minister position, and then later enticing Abacha to take the

Defence Minister position in combination with the position of Chairman, Joint

Chiefs of Staff. In exchange, Abacha would vacate the position

of Chief of Army Staff.

This

delicate two step process, initiated on December 29, 1989, was complicated by

negative reactions to the step one removal of Lt. General Domkat Bali and the

perception that the changes affected the religious balance of power in the

military. Bali himself refused to accept his demeaning redeployment

as Minister of Internal Affairs, where he would take over from Brigadier John

Shagaya, a junior officer from the same Langtang area of Plateau

State. Instead he chose to retire ten days later.

In April

1990, citing a laundry list of complaints, junior officers led by Lt. Col. G

Nyiam, Major Saliba Mukoro and Major Gideon Orkar staged an attempted coup,

which eventually failed. One of their complaints was “The

shabby and dishonourable treatment meted on the longest serving Nigerian

General in the person of General Domkat Bali, who in actual fact had given

credibility to the Babangida administration”.

By all

accounts, most of the credit for rallying the resistance and crushing this coup

attempt goes to Lt. Gen. Sani Abacha, who was at that time the Chief of Army

Staff and concurrent Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff. After

the rebellion was crushed, Abacha went on radio to reassure the country. Among

other things, he said:

"I, Lieutenant-General Sani Abacha, Chief of Army Staff, Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff, have found it necessary to address you once again in the course of our nation's history. In view of the unfortunate, development early this morning, I'm in touch with the CGS, Service Chiefs, GOCs, FOCs, AOCs, of the armed forces and they have all pledged their unflinching support and loyalty to the federal military government of General Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida who is perfectly safe and with whom I am in contact…………..……….No amount of threat or blackmail will detract the federal military government's attention in this regard. We are set to hand over power to a democratically elected government in 1992. I wish to assure all law-abiding citizens that the situation is now under control and people should go about pursuing their lawful interest.

Long live the Federal Republic of Nigeria.Thank you."

General Abacha’s role in saving the Babangida regime in 1990 bought him huge

stock, not only with Babangida himself but also with a significant number of

other “IBB Boys”. It marked the beginning of the rise of Sani Abacha

and the beginnings of his own independent client network, separate from the

umbilical cord that tied him into the maternal Babangida

bandwagon. His own independent network would later become known as

“Abacha Boys”, based mainly, but not exclusively, around officers from the Kano

area.

After a

lull during which Babangida was very nervous and lacked confidence, he later

resumed the old plan to replace Abacha as Chief of Army Staff. In

September 1990, after two batches of executions of “Orkar coup convicts” had

been carried out, Babangida ceded his position as Minister of Defence to

General Abacha who was to combine it with his position as Chairman, Joint

Chiefs of Staff. Some observers feel that an unwritten part of this

new arrangement was that Abacha would be left alone to do as he pleased with

defence funds while Babangida ran the rest of the government. To

crystallize the new “space” created for General Abacha as the “Defence Czar”,

he stayed behind in Lagos when Babangida moved to the new capital of Abuja in

1991. It was as if the country had two governments.

|

| Maj. Gen. Chris Alli (retd.) |

Abacha

retained the combined positions of Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff and Defence

Minister until August 26, 1993. After the events of April 1990,

Babangida was often quoted as referring to him as “Khalifa”, meaning

“successor”. Meanwhile, it should be noted that although Vice-Admiral Aikhomu was

transitioned from the office of Chief of General Staff and made the

Vice-President in 1990 to President Babangida, that slot was actually initially

proposed to Chief Ernest Shonekan, a civilian United African Company (UAC)

Executive.

THE

POLITICAL COUNT DOWN

Others

have written extensively about the political countdown and endless transition

of the Babangida regime. As is well known, the date of the final handing over

of power was shifted from 1990 to 1992 and then 1993. I shall

present a brief overview and highlight those aspects that show the hand of

General Abacha as a behind the scenes manipulator.

Based in

part on the report of the Political Bureau, which was originally set up in

1986, a two-party system (one "a little to the right" and the other

"a little to the left.”) was created in October

1989. They were the National Republican Convention (NRC) and

the Social Democratic Party (SDP). Both parties were run and financed by the

Government, which also arrogated to itself the right to write their party

constitutions. The constitutional context was the 1989 Constitution

(Decree #12 of 1989), based on work done by a Constitution Review Committee,

ratified by the Constituent Assembly and amended by the Armed Forces Ruling

Council. Among the eleven amendments imposed by the AFRC, three were

defence and security related. One removed the National Assembly’s

control over national security because, (according to the AFRC), it

"exposes the chief executives and the nation to clear impotence in the face

of threats to security". The second deleted certain

provisions establishing an Armed Forces Service Commission to supervise

implementation of the federal-character principle. The third

amendment removed Section 1 (4) of the draft constitution, which had outlawed

coups and classified them as criminal.

Initially,

based on Decree #25 of 1987 amended by Decree # 9 of 1989, there was

a ban on all former politicians and top officeholders since 1960, particularly

those previously found guilty of abuse of office. However,

both decrees were repealed in December 1991, initially under pressure from

‘northern elders’ but ultimately to ‘create a level playing field for all

ethnic groups’. Similarly, based on Decree #19 of 1987 and amended

by Decree #26 of 1989, the plan was for presidential elections in November

1992. However, as a result of alleged malpractices during party

primaries in Sept 1992, primaries were cancelled altogether in October 1992,

major contenders frozen out, and the timetable shifted to 1993. Local, State

and National committees of both parties were dissolved and replaced by

caretaker committees. The Babangida government later announced that they would

be audited.

The

driving principle behind all of this was Babangida’s fear of powerful,

financially independent politicians and his secret desire to plant handpicked,

“controllable” newbreed politicians in state government houses and legislative

positions all over the country as a civilian base for a diarchy which he would

head at the center. Those who lost out in the cancellation of the

1992 Presidential primaries and were banned included late Major General

Yar’Adua (rtd) who won the SDP nomination hands down, and Chief Olu Falae;

Alhaji Adamu Ciroma and Alhaji Umaru Shinkafi were about to go in for a run-off

for the NRC nomination. They too were banned.

A few

weeks later, on November 17, 1992, General Babangida dissolved the AFRC and,

after a pregnant pause, created the National Defence and Security Council

(NDSC) on January 2, 1993. A civilian Transitional Council was also

set up to replace the Council of Ministers and win back waning public

confidence in the “transition program” following the failed Presidential

Primaries. Its Chairman was Chief Ernest Shonekan, also known as

“Head of Government”. Empowered by Decree #54 of 1992 Constitution

(Suspension and Modification) [Amendment], the Transitional Council shared

joint responsibility with the National Defence and Security Council to ensure a

smooth and successful handover to civilians. It was after all of

this that Alhaji Bashir Othman Tofa and Chief Moshood Kashimawo Olawale Abiola

later emerged as the Presidential contenders from the NRC and SDP

respectively. Strangely, though, neither men internalized the bitter

experience of men before them like Shehu Yar’Adua, Olu Falae, Umaru Shinkafi,

Adamu Ciroma and Bamanga Tukur, all of whom had been led on by Babangida but

ultimately betrayed at the end.

All of

this was being monitored by the security services - as well as General Sani

Abacha, who later told confidants that Babangida had been toying with the idea

of ruling Nigeria for 30 years. When Chief Abiola first showed

interest in running for the Presidency, certain “IBB Boys” (including Abacha)

expressed concern and approached Babangida to find some way to ban Abiola from

taking part. However, based on a security report which falsely

projected Alhaji Babagana Kingibe as the likely winner of the SDP Presidential

primary convention in Jos, Babangida assured his concerned “military boys” that

Abiola would not prevail and thus there was no need for fear. On the

other hand he simultaneously assured Abiola that he could run for office if he

so wished and would have no problems if he won fair and square. He

did not, as far as is publicly known, tell Abiola at that early stage that

there were restive northern officers opposed to his political ambitions, nor

did he tell his “caucus” officers that he had given his word to Abiola that he

could run for office. Interestingly, Abiola himself was independently

familiar with most members of the Babangida military caucus, either as business

associates or as a financial sponsor of previous coups (in 1983 and 1985) in

which they had played key roles.

As things

turned out, to the consternation of military officers - like Abacha - who were

opposed to Chief Abiola, Abiola narrowly won the SDP nomination at the Jos

convention, overcoming determined opposition from a motley group of SDP

Governors and disgruntled former aspirants. However, security sources

reported allegations of massive vote buying. Concerned officers approached

Babangida to use the report as an excuse to ban Abiola and stop the process at

that stage before it evolved to formal national

elections. Meanwhile, as the June elections came nearer, against a

backdrop of anti-military agitation by students and workers groups, General

Olusegun Obasanjo and Chief Anthony Enahoro publicly expressed doubts over the

sincerity of military’s intention to leave power. Caught between an

undercurrent of public suspicions that he had a “hidden agenda” and behind the

scene pressure from some powerful elements of his military caucus to scuttle

the transition again, Babangida initially resisted the military

pressure. Alhaji Baba Gana Kingibe emerged after difficult

negotiations as Abiola’s running mate while Dr. Sylvester Ugoh was chosen as

Tofa’s Vice Presidential candidate.

It must

be mentioned, however, that the voice of the military was by no means uniform.

There were officers, like Lt. Gen Salihu Ibrahim, General Ishola Williams,

Brigadier MC Alli, Colonel Abubakar Umar and a few others who genuinely wanted

a disengagement of the military from politics. Some people

claim Lt. General Oladipupo Diya was also not in favor of the military

perpetuating itself at this stage. Other officers preferred one

candidate versus the other, while a small clique did not want to leave power

for either candidate. This clique included Lt. Gen. Dogonyaro,

Brigadier David Mark, Brigadier Stephen Anthony Ukpo, Brigadier John Shagaya,

Brigadier Halilu Akilu and a few others, all of whom were “IBB

boys”. What is really fascinating is how General Abacha concealed

his real motives and intentions from most military officers. At the

few senior officer conferences he attended, Abacha would typically remain

quiet. He preferred to express his strong views to Babangida directly and

privately, while quietly mobilizing opinion behind the scenes and maintaining

discrete contact with civilian leaders of thought who were opposed to the elections

in general and to Chief Abiola specifically. Meanwhile, to those

unfamiliar with their inner tensions, he positioned himself as the guarantor of

the Babangida regime. Further on in this essay, the strategic

brilliance of Abacha’s concealment will be apparent. Major General

MC Alli, for example, says that Abacha “had the patience of a hook-line

fisherman or a bush hunter, and the memory of an elephant and a native cunning

to match.”

In

addition to this cacophony of discordant but troubling military voices there

were powerful civilian pressures, notably from then Sultan of Sokoto, Ibrahim

Dasuki as well as other Emirs who allegedly did not like or trust either Tofa

or Abiola. In the background, personalities who had been banned or schemed

out from contesting as a result of government fiat were also opposed to the

elections. These included late Major General Shehu Yar’Adua and

Alhaji Abubakar Rimi. Funny enough Alhaji Bashir Tofa who was also a

candidate, supported by some elements within the NRC, also joined the bandwagon

to boycott and/or cancel the elections. Then there were mischievous

campaigners, like the Association for Better Nigeria (ABN) which wanted the

military to hold on to power. All these internal groups and persons

working hard to scuttle the elections altogether were opposed by foreign

countries like Britain and the US which wanted the military to leave

power.

Nevertheless,

on June 10, 1993, ignoring ouster clauses in Decree #13 of 1993 and Decree #19

of 1987, Justice Bassey Ikpeme of the Abuja High Court granted a motion brought

by the ABN to restrain the Electoral Commission (NEC) from conducting the

election. However, citing lack of jurisdictional authority, General

Babangida initially chose to ignore the court, which is why the NEC went ahead

to conduct the election on June 12, which was later said to be ‘free and fair’.

Nowa Omoigui

nowa_o@yahoo.com

Comments

Post a Comment